Saturday, February 24, 2007

La Isabela: The Mysterious Case of Columbus's Silver Ore

Archaeology: Silver-bearing ore found at the settlement founded by Christopher Columbus's second expedition was not mined in the Americas, new research reveals. The ore that researchers excavated from the settlement, La Isabela, came from Spain, said Alyson Thibodeau, who analyzed the ores.

"What appeared to be the earliest evidence of European finds of precious metals in the New World turned out not to be that at all," said David J. Killick. "It's a very different story."

Samples of galena, a silver-bearing lead ore and worked pieces of lead recovered from the archaeological dig at La Isabela. Copyright 1998. James Quine of the Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida.

The explorers brought the Spanish ore to La Isabela to use for comparison when assaying the new ores they expected to find, the researchers surmise. The expedition's purpose was discovering precious metals.

But by 1497, La Isabela's remaining settlers, having found no gold or silver, were desperate to salvage something of value from the failed settlement. They were reduced to extracting silver from the galena they brought from Spain, the researchers said.

"This part of the story of Columbus's failed settlement is one that couldn't be found in the historical documents," said Thibodeau, a geosciences graduate student at The University of Arizona (UA) in Tucson. "We could never have figured this out without applying the techniques of physical sciences to the archaeological artifacts."

Thibodeau, Killick, a UA associate professor of anthropology, and their colleagues will publish their article, "The Strange Case of the Earliest Silver Extraction by European Colonists in the New World," [1] in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences during the week of February 19, 2007.

The other authors are UA's Joaquin Ruiz, John T. Chesley and Ward Lyman; Kathleen Deagan of the University of Florida in Gainesville; and Jose M. Cruxent (deceased). The National Science Foundation, Direccion Nacional de Parques de la Republica Dominicana, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Geographic Society and the W. M. Keck Foundation helped fund the research.

Co-authors Kathleen Deagan and Jose M. Cruxent standing by the foundations of La Isabela's royal storehouse, where metallurgical activities took place. Copyright 1998. James Quine, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida.

La Isabela, the first European town in the New World, was established by Columbus's second expedition in 1494 on the northern coast of the present Dominican Republic (Hispaniola).

The approximately 1500 members of the expedition expected to make their fortunes by finding precious metals but instead found hurricanes, hunger and disease. Columbus was recalled to Spain in 1496, and the few hundred remaining inhabitants abandoned the town in 1498.

Archaeologists excavating the site in the late 1980s and early 1990s found about 100 pounds of galena, a silver-bearing lead ore, and more than 200 pounds of metallurgical slag. The ore and slag were associated with a small furnace near the alhondiga, a building (or 'warehouse') for the storage and protection of royal property.

Archaeologist Deagan sent pieces of the material to archaeometallurgist Killick for analysis.

The slag turned out to be lead silicate - the end product of an improvised smelting process, Killick said, adding "Lead silicate is good for nothing." Other smelting processes used at the time could recapture the ore's lead so it could be used for musket balls and as cladding for ships.

"Why waste the lead?" Killick said. "Normally, they would smelt the galena to lead."

Killick and graduate student Ward Lyman examined the slag under a microscope and saw specks of silver, suggesting that Columbus's followers were trying to extract silver from the galena by removing all the lead.

"We thought, 'Fantastic!' The first evidence of Europeans prospecting for silver in the New World."

By reviewing the accounts of Columbus's second voyage, Thibodeau found the expedition had visited islands where geologists now know galena occurs.

It was puzzling that the documents made no mention of finding such ore, Killick said. Maybe it didn't seem to be enough metal to mention or maybe some members of the expedition were trying to hide the discovery.

Thibodeau then used lead isotope analysis to determine where La Isabela's galena originated. The ratio of the different forms, or isotopes, of lead provides a kind of fingerprint that can indicate the source of a rock.

"We're looking at something about the rock's chemistry and using that to tell us where it came from," she said. "It's like Antiques Roadshow where the appraiser looks at some characteristic of an antique and says, 'This was made by so-and-so at such-and-such a time.'"

Figuring out that the galena came from Spain led to the question, why bring ore? The documents report that the expedition also brought lead.

By contacting an expert in medieval chemistry, the scientists learned that a common practice of the time was mixing galena with powdered ores suspected of having gold or silver. The process provided an assay of the gold or silver in the newly discovered hunk of ore by comparing it with galena containing a known, small quantity of silver.

Given that the expedition purpose was discovering new sources of precious metals, it makes sense that the members toted along materials to assess their discoveries."It was a nice detective story," Killick said. "We think we've solved this one."

But there are more archaeological puzzles out there, Thibodeau said.

"Archaeology tells us what might be an interesting question to ask - and the physical sciences gives us a way to answer the question," Thibodeau said.

Source (Adapted): University of Arizona PR February 19, 2007

-------

[1] The strange case of the earliest silver extraction by European colonists in the New World

A. M. Thibodeau, D. J. Killick, J. Ruiz, J. T. Chesley, K. Deagan, J. M. Cruxent and W. Lyman

Published online before print February 21, 2007

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.0607297104

La Isabela, the first European town in the New World, was established in 1494 by the second expedition of Christopher Columbus but was abandoned by 1498. The main motive for settlement was to find and exploit deposits of precious metals. Archaeological evidence of silver extraction at La Isabela seemed to indicate that the expedition had located and tested deposits of silver-bearing lead ore in the Caribbean. Lead isotope analysis refutes this hypothesis but provides new evidence of the desperation of the inhabitants of La Isabela just before its abandonment.

Recent posts include:

"The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 1)"

"Ancient coin challenges myth of Cleopatra's beauty (+ related video)"

"The key to Stradivari's tone"

"Climate shift helped destroy China's Tang dynasty"

Technorati: archaeology, silver ore, settlement, christopher, columbus, la isabela, hispaniola, dominican republic, galena, new world, spain, anthropology, science

Add to: CiteUlike | Connotea | Del.icio.us | Digg | Furl | Newsvine | Reddit | Yahoo

Thursday, February 22, 2007

The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 3)

A three part article.

The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 1) contains:

'The Bermuda Triangle: Beneath the Waves' BBC Television Documentary Video, a link to a BBC radio program on gas hydrates and their possible relevance to the Bermuda Triangle mystery, plus:

1) Bermuda Triangle Fact Sheet

2) History of USS Cyclops + Images

Part 2 contains::

3) The Loss Of Flight 19

4) "Lost Patrol"

This post consists of:

5) In Search of.. The Bermuda Triangle (Video - Leonard Nimoy)

6) "Exorcizing the Devil's Triangle"

One of the Flight 19 Avengers lost on Flight 19 (No-one pictured was on the flight - US Navy)

5) In Search of.. The Bermuda Triangle (Video - Leonard Nimoy)

Part of the In Search Of series, this documentary takes a detailed look at the mysteries behind the legend of the Bermuda Triangle. Narrated by series host Leonard Nimoy, this video features interviews with some believers and non-believers who discuss the history and the controversy about this area in the Atlantic Ocean. Scientists and some eyewitnesses try to separate fact from fiction as they talk about their personal beliefs and experiences with the triangle. There are also dramatizations of some of the supposed missing planes and ships, including speculation as to where these lost crafts disappeared and what really happened to them in the middle of the ocean waters. - Cecilia Cygnar, All Movie Guide [Source: Movies Answers.com]

-------

The following information is courtesy of the US Naval Historical Center:

6) "Exorcizing the Devil's Triangle" Sealift no. 6 (Jun. 1974): 11-15. By Howard L. Rosenberg

During the past century more than 50 ships and 20 aircraft sailed into oblivion in the area known as the Devil's Triangle, Bermuda Triangle, Hoodoo Sea, or a host of other names.

Exactly what happened to the ships and aircraft is not known. Most disappeared without a trace. Few distress calls and little, if any, debris signaled their disappearance.

Size of the triangle is dictated by whoever happens to be writing about it, and consequently what ships and the number lost depends largely on which article you read.

Vincent Gaddis, credited with putting the triangle "on the map" in a 1964 Argosy feature (Argosy February 1964 p. 28-29, 116-118: The Deadly Bermuda Triangle - Full Text), described the triangle as extending from Florida to Bermuda, southwest to Puerto Rico and back to Florida through the Bahamas. Another author puts the apexes of the triangle somewhere in Virginia, on the western coast of Bermuda and around Cuba, Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. Sizes of the areas described ranged from 500,000 to 1.5 million square miles.

Whatever the size or shape, there supposedly is some inexplicable force within it that causes ships and planes to vanish.

According to Richard Winer, who recently completed a TV film documentary on the area, one "expert" he interviewed claims the missing ships and planes are still there, only in a different dimension as a result of a magnetic phenomenon that could have been set up by a UFO (Unidentified Flying Object).

Winer is currently writing a book on the subject and has traveled most of the area in his sailboat. He confesses he "never saw anything unusual."

Winer's TV program dealt mostly with the strange disappearance in 1945 of five Navy TBM Avengers with 14 fliers who flew from Ft. Lauderdale into the triangle never to return. A PBM Mariner with a 13-man crew was sent out to search for the fliers. It too, never returned.

Few have really dug into all the aspects of this mystery, but many are content to attribute the loss of Flight 19 to some mysterious source, like UFOs. Michael McDonnel did do some digging. In an article he wrote for the June 1973 edition of Naval Aviation News (see Part 2), he suggested the most realistic answer to the loss of Flight 19 was simple, that after becoming lost, they ran out of gas. Many question that possibility by asking, "How could such experienced pilots get lost? How could all the compasses be wrong?"

If the planes were flying through a magnetic storm, all compasses could possibly malfunction. Actually, man's knowledge of magnetism is limited. We know how to live with it and escape it by going into space, but, we really don't know what exactly it is.

As for the pilots' experience, Flight 19 was a training flight. Though advanced, it was still training. Even the most "experienced" pilots make mistakes.

McDonnel concludes his article with the statement, "Former TBM pilots that we questioned express the opinion that the crew of an Avenger attempting to ditch at night in a heavy sea would almost certainly not survive the crash. And this, we feel was the case with Flight 19. The aircraft most probably broke up on impact and those crewmen who might have survived the crash would not have lasted long in cool water."

The PBM Mariner was specifically designed as a rescue plane with the ability to remain aloft for 24 hours. But the Mariners were nicknamed "flying gas tanks" by those who flew them. It was common for a pilot to search the crew members before each flight for matches or cigarette lighters because gas fumes often were present. After this Mariner disappeared, the Navy soon grounded all others.

Another mysterious disappearance that baffles researchers is that of the SS Marine Sulphur Queen. Bound for Norfolk, Va. from Beaumont, Texas, the tanker was last heard from on Feb. 3, 1963, when she routinely radioed her position. The message placed her near Key West in the Florida Straits.

Three days later, US Coast Guard searchers found a solitary life jacket bobbing in a calm sea 40 miles southwest of the tanker's last known position. Another sign of the missing tanker or her 39-man crew has ever been found.

The absence of bodies might be explained by the fact that the waters are infested with sharks and barracuda. As for the tanker, she was carrying 15,000 long tons of molten sulphur contained in four metal tanks, each heated to 275 degrees Fahrenheit by a network of coils connected to two boilers.

No one knows for sure whether she blew up, but it is a possibility. If gas escaped from the tanks and poisoned the crew, the radio officer may have not had time to send a distress call before being overcome. The slightest spark could have set the leaking sulphur afire in an instant.

Writing in the Seamen's Church Institute of New York's magazine, The Lookout, Paul Brock said that officers on a Honduras flag banana boat "reported to the Coast Guard that their freighter ran into a 'strong odor' 15 miles off Cape San Antonia, the western tip of Cuba, just before dawn on February 3. The odor was acrid.'"

Brock speculates that they could have smelled the fumes coming from the Sulphur Queen "floating somewhere over the horizon, her crew dead and her cargo blazing."

According to Brock, T-2 tankers like the Sulphur Queen had a history of battle failure. He said that "during the preceding years, three T-2s had split in half." Brock also cites a case in December 1954 when a converted Navy LST, the Southern District, was heading up the North Carolina coastline when she disappeared without a trace or distress call. Her cargo was powdered sulphur.

One of the most celebrated stories of Devil's Triangle victims, is that of USS Cyclops which disappeared in March of 1918.

In his television program, Richard Winer indicated the captain of the Cyclops was rather eccentric. He was reputedly fond of pacing the quarterdeck wearing a hat, a cane and his underwear. Prior to the Cyclops disappearance there was a minor mutiny by some members of the crew which was promptly squelched by the captain and the perpetrators were sent below in irons. None of this really offers a clue to what happened to the collier Cyclops, but it suggests something other than a mysterious force might have led to her doom.

According to Marshall Smith writing in Cosmopolitan, September 1973, "theories ranged from mutiny at sea to a boiler explosion which carried away the radio shack and prevented any distress call." One magazine, Literary Digest, speculated that a giant octopus rose from the sea, entwined the ship with its tentacles and dragged it to the bottom. Another theory was that the shipped suddenly turned turtle in a freak storm, trapping all hands inside.

Fifty years later, novelist Paul Gallico used the idea as the peg for a novel called The Poseidon Adventure which was made into a successful movie in 1972.

Cyclops was assigned to the Naval Overseas Transportation Service, which became the Naval Transportation, which merged with the Army Transport Service to become the Military Sea Transportation Service and then Military Sealift Command. When she sailed she was loaded with 10,800 tons of manganese ore bound for Baltimore from Barbados in the West Indies.

Information obtained from Germany following World War I disproved the notion that enemy U-boats or mines sank the Cyclops. None were in the area.

Another story concerns the loss of the nuclear submarine USS Scorpion in the Devil's Triangle. It is impossible to stretch even the farthest flung region of the triangle to include the position of the lost sub.

USS Scorpion. Lost with all hands, 22nd May 1968

Truth is, Scorpion was found by the MSC oceanographic ship USNS Mizar about 400 miles southwest of the Azores, nowhere near the Devil's Triangle. Its loss was attributed to mechanical failure, not some demonic denizen of the deep.

There are literally thousands of cases of lost ships ever since primitive man dug a canoe out of the trunk of a tree and set it in the water. Why all this emphasis on the Devil's Triangle? It's difficult to say.

It would seem that, historically, whenever man was unable to explain the nature of the world around him, the problems he faced were said to be caused by gods, demons, monsters and more recently, extra-terrestrial invaders.

Before Columbus set sail and found the Americas, it was believed that the world was flat and if you sailed too far west, you would fall off the edge. That reasoning prevails concerning the Devil's Triangle. Since not enough scientific research has been done to explain the phenomenon associated with the area, imagination takes over. UFOs, mystical rays from the sun to the lost Continent of Atlantis, giant sea monsters and supernatural beings are linked to the mysterious disappearances in the triangle.

To someone unprepared to take on the immense work of scientific research, supernatural phenomenon make for an easy answer. But, it is amazing how many supernatural things become natural when scientifically investigated.

There are a number of natural forces at work in the area known as the Devil's Triangle, any of which could, if the conditions were right, bring down a plane or sink a ship.

Many reputable scientists refuse to talk to anyone concerning the Devil's Triangle simply because they do not want their good names and reputations associated with notions they consider ridiculous.

One expert on ocean currents at Yale University, who asked not to be identified, exploded into laughter at the mention of the triangle and said, "We confidently, and without any hesitation, often go to sea and work in that area." Another scientist refused to talk about it.

Atmospheric aberrations are common to jet age travelers. Few have flown without experiencing a phenomenon known as clear air turbulence. An aircraft can be flying smoothly on a beautifully clear day and suddenly hit an air pocket or hole in the sky and drop 200 to 300 feet.

Lt. Cmdr. Peter Quinton, meteorologist and satellite liaison officer with the Fleet Weather Service at Suitland, Md., said, "You can come up with hundreds of possibilities and elaborate on all of them and then come up with hundreds more to dispute the original ones."

"It's all statistical," he said, "there's nothing magical about it." According to Quinton, the Bermuda Triangle is notorious for unpredictable weather. The only things necessary for a storm to become a violent hurricane are speed, fetch (the area the wind blows over) and time. If the area is large enough, a thunderstorm can whip into a hurricane of tremendous intensity. But hurricanes can usually be spotted by meteorologists using satellite surveillance. It is the small, violent thunderstorms known as meso-meteorological storms that they can't predict since they are outside of normal weather patterns. These are tornadoes, thunderstorms and immature tropical cyclones.

They can occur at sea with little warning, and dissipate completely before they reach the shore. It is highly possible that a ship or plane can sail into what is considered a mild thunderstorm and suddenly face a meso-meteorological storm of incredible intensity.

Satellites sometimes cannot detect tropical storms if they are too small in diameter, or if they occur while the satellite is not over the area. There is a 12-hour gap between the time the satellite passes over a specific part of the globe until it passes again. During these 12 hours, any number of brief, violent storms could occur.

Quinton said, "Thunderstorms can also generate severe electrical storms sufficient to foul up communication systems." Speaking of meso-meteorological storms, which she dubbed "neutercanes," Dr. Joanne Simpson, a prominent meteorologist at the University of Miami, said in the Cosmopolitan article that "These small hybrid type storm systems arise very quickly, especially over the Gulf Stream. They are several miles in diameter, last a few minutes or a few seconds and then vanish. But they stir up giant waves and you have chaotic seas coming from all directions. These storms can be devastating."

An experienced sailor herself, Dr. Simpson said on occasion she has been "peppered by staccato bolts of lightning and smelled- the metallic odor of spent electricity as they hit the water, then frightened by ball lightning running off the yards." Sailors have been amazed for years by lightning storms and static electricity called "St. Elmo's Fire."

Aubrey Graves, writing in This Week magazine, August 4, 1964, quotes retired Coast Guard Capt. Roy Hutchins as saying, "Weather within the triangle where warm tropical breezes meet cold air masses from the arctic is notoriously unpredictable." "You can get a perfectly good weather pattern, as far as the big weather maps go, then go out there on what begins as a fine day and suddenly get hit by a 75-knot squall. They are localized and build up on the spot, but they are violent indeed."

Many boatmen, Hutchins said, lack understanding of the velocity of that "river within the ocean" (Gulf Stream) which at its axis surges north at four knots. "When it collides with strong northeast winds, extremely stiff seas build up, just as in an inlet when the tide is ebbing against an incoming sea."

"The seas out there can be just indescribable. The waves break and you get a vertical wall of water from 30 to 40 feet high coming down on you. Unless a boat can take complete submergence in a large, breaking sea, she can not live."

Last year, the Coast Guard answered 8,000 distress calls in the area, 700 a month or 23 a day. Most problems could have been avoided if caution had been used. The biggest trouble comes from small boats running out of gas. According to the Coast Guard, an inexperienced sailor is looking for trouble out there. A small boat could be sucked into the prop of a big tanker or swamped in a storm and never be seen again.

Another phenomenon common in the region is the waterspout. Simply a tornado at sea that pulls water from the ocean surface thousands of feet into the sky, the waterspout could "wreck almost anything" said Allen Hartwell, oceanographer with Normandeau Associates.

Hartwell explained that the undersea topography of the ocean floor in the area has some interesting characteristics. Most of the sea floor out in the Devil's Triangle is about 19,000 feet down and covered with deposition, a fine-grained sandy material. However, as you approach the East Coast of the United States, you suddenly run into the continental shelf with a water depth of 50 to 100 feet. Running north along the coast is the Gulf Stream which bisects the triangle carrying warm tropical water.

Near the southern tip of the triangle lies the Puerto Rico Trench which at one point is 27,500 feet below sea level. It's the deepest point in the Atlantic Ocean and probably holds many rotting and decaying hulks of Spanish treasure galleons.

Many articles concerning the triangle have made the erroneous statement that the Navy formed Project Magnet to survey the area and discover whether magnetic aberrations do limit communications with ships in distress, or contribute to the strange disappearance of ships and aircraft.

Truth is that Navy's Project Magnet has been surveying all over the world for more than 20 years, mapping the earth's magnetic fields. According to Henry P. Stockard, project director, "We have passed over the area hundreds of times and never noticed any unusual magnetic disturbances."

Also passing through the Devil's Triangle is the 80th meridian, a degree of longitude which extends south from Hudson Bay through Pittsburgh then out into the Triangle a few miles east of Miami. Known as the agonic line, it is one of two places in the world where true north and magnetic north are in perfect alignment and compass variation is unnecessary. An experienced navigator could sail off course several degrees and lead himself hundreds of miles away from his original destination.

This same line extends over the North Pole to the other side of the globe bisecting a portion of the Pacific Ocean east of Japan.

This is another part of the world where mysterious disappearances take place and has been dubbed the "Devil Sea" by Philippine and Japanese seamen. Noted for tsunami, the area is considered dangerous by Japanese shipping authorities. Tsunami, often erroneously called tidal waves, are huge waves created by underground earthquakes. These seismic waves have very long wave lengths and travel at velocities of 400 miles per hour or more. In the open sea they may be only a foot high. But as they approach the continental shelf, their speed is reduced and their height increases dramatically. Low islands may be completely submerged by them. So too may ships sailing near the coast or above the continental shelf.

Quite a bit of seismic activity occurs off the northern shoreline of Puerto Rico. Seismic shocks recorded between 1961 and 1969 had a depth of focus ranging from zero to 70 kilometers down. Relatively shallow seaquakes could create tsunamis similar to those in the Pacific Ocean, but few have been recorded.

A distinct line of shallow seaquake activity runs through the mid-Atlantic corresponding with the features of the continental shelf of the Americas.

Some claim we know more about outer space than we do about inner space, including the oceans. If that is true, much information has yet to be developed concerning the Devil's Triangle. As recently as 1957 a deep counter-current was detected beneath the Gulf Stream with the aid of sub-surface floats emitting acoustic signals. The Gulf Stream and other currents have proved to consist of numerous disconnected filaments moving in complex patterns.

What it all adds up to is that the majority of the supernatural happenings offered as explanations for the Devil's Triangle mysteries amount to a voluminous mass of sheer hokum, extrapolated to the nth degree.

Mysteries associated with the sea are plentiful in the history of mankind. The triangle area happens to be one of the most heavily traveled regions in the world and the greater the number of ships or planes, the greater the odds that something will happen to some.

Each holiday season the National Safety Council warns motorists by predicting how many will die on the nation's highways. They are usually quite accurate, but, no monsters kill people on highways, only mistakes.

Seafarers and aircraft pilots also make mistakes. Eventually scientists will separate fact from the fiction concerning the Devil's Triangle. Until then, we can only grin and bear the ministrations of madness offered by triangle cultists.

If you happen to be passing through the triangle while reading this article, don't bother to station extra watches to keep a wary eye out for giant squids. Better to relax and mull over the words of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow:

"Wouldst thou," so the helmsman answered,

"Know the secret of the sea?"

Only those who brave its dangers,

Comprehend its mystery.

-------

Recent posts include:

"The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 1)"

"The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 2)"

"Japan Researchers Film Live Giant Squid (Video)"

"Hunting behavior of Large Bioluminescent Squid (Video)"

Technorati: st elmo's fire, atlantic, ocean, bermuda triangle, florida, search, leonard, nimoy, video, bbc, television, 1945, uss, cyclops, scorpion, flight 19, weather, lost, devil, bermuda, puerto rico, miami

Add to: CiteUlike | Connotea | Del.icio.us | Digg | Furl | Newsvine | Reddit | Yahoo

Wednesday, February 21, 2007

The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 2)

A three part article.

The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 1) contains:

'The Bermuda Triangle: Beneath the Waves' BBC Television Documentary Video, a link to a BBC radio program on gas hydrates and their possible relevance to the Bermuda Triangle mystery, plus:

1) Bermuda Triangle Fact Sheet

2) History of USS Cyclops + Images

This post consists of:

3) The Loss Of Flight 19

4) "Lost Patrol"

Part 3 consists of:

5) In Search of.. The Bermuda Triangle (Video - Leonard Nimoy)

6) "Exorcizing the Devil's Triangle"

A NASA image showing the three points of the Bermuda Triangle: Miami, Florida, Bermuda, and San Juan, Puerto Rico.

The following information is courtesy of the US Naval Historical Center:

3) The Loss Of Flight 19

Prepared by the Operational Archives Branch, Naval Historical Center

At about 2:10 p.m. on the afternoon of 5 December 1945, Flight 19, consisting of five TBM Avenger Torpedo Bombers (manufactured by the Eastern Aircraft under license from Grumman) departed from the U. S. Naval Air Station, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, on an authorized advanced overwater navigational training flight. They were to execute navigation problem No. 1, which is as follows: (1) depart 26 degrees 03 minutes north and 80 degrees 07 minutes west and fly 091 degrees (T) distance 56 miles to Hen and Chickens Shoals to conduct low level bombing, after bombing continue on course 091 degrees (T) for 67 miles, (2) fly course 346 degrees (T) distance 73 miles and (3) fly course 241 degrees (T) distance 120 miles, then returning to U. S. Naval Air Station, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Flight plan for Flight 19 on December 5, 1945 (red line). Red 'X' indicates possible location of Flight 19 based on final radio fix. Yellow line indicates path of Training 49; yellow 'X' is probable site of explosion. Image: NASA/Wiki.

In charge of the flight was a senior qualified flight instructor, piloting one of the planes. The other planes were piloted by qualified pilots with between 350 and 400 hours flight time of which at least 55 was in TBM type aircraft. The weather over the area covered by the track of the navigational problem consisted of scattered rain showers with a ceiling of 2500 feet within the showers and unlimited outside the showers, visibility of 6-8 miles in the showers, 10-12 otherwise. Surface winds were 20 knots with gusts to 31 knots. The sea was moderate to rough. The general weather conditions were considered average for training flights of this nature except within showers.

A radio message intercepted at about 4 p.m. was the first indication that Flight 19 was lost. This message, believed to be between the leader on Flight 19 and another pilot in the same flight, indicated that the instructor was uncertain of his position and the direction of the Florida coast. The aircraft also were experiencing malfunction of their compasses. Attempts to establish communications on the training frequency were unsatisfactory due to interference from Cuba broadcasting stations, static, and atmospheric conditions. All radio contact was lost before the exact nature of the trouble or the location of the flight could be determined. Indications are that the flight became lost somewhere east of the Florida peninsula and was unable to determine a course to return to their base. The flight was never heard from again and no trace of the planes were ever found. It is assumed that they made forced landings at sea, in darkness somewhere east of the Florida peninsula, possibly after running out of gas. It is known that the fuel carried by the aircraft would have been completely exhausted by 8 p.m. The sea in that presumed area was rough and unfavorable for a water landing. It is also possible that some unexpected and unforeseen development of weather conditions may have intervened although there is no evidence of freak storms in the area at the time (1945 Hurricane/Tropical Data for Atlantic).

All available facilities in the immediate area were used in an effort to locate the missing aircraft and help them return to base. These efforts were not successful. No trace of the aircraft was ever found even though an extensive search operation was conducted until the evening of 10 December 1945, when weather conditions deteriorated to the point where further efforts became unduly hazardous. Sufficient aircraft and surface vessels were utilized to satisfactorily cover those areas in which survivors of Flight 19 could be presumed to be located.

One search aircraft was lost during the operation. A PBM patrol plane which was launched at approximately 7:30 p.m., 5 December 1945, to search for the missing TBM's. This aircraft was never seen nor heard from after take-off. Based upon a report from a merchant ship off Fort Lauderdale which sighted a "burst of flame, apparently an explosion, and passed through on oil slick at a time and place which matched the presumed location of the PBM, it is believed this aircraft exploded at sea and sank at approximately 28.59 N; 80.25 W. No trace of the plane or its crew was ever found.

The Operational Archives Branch, Naval Historical Center has placed the Board of Investigation convened at NAS Miami to inquire into the loss of the 5 TBM Avengers in Flight 19 and the PBM aircraft on microfilm reel, NRS 1983-37.

-------

4) "Lost Patrol" Naval Aviation News June 1973, 8-16. By Michael McDonell

At 1410 on 5 December 1945, five TBM Avengers comprising Flight 19 rose into the sunny sky above NAS Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Turning east the formation headed out over the Atlantic on the first leg of a routine exercise from which neither the 14 men of Flight 19 nor the 13-man crew of a PBM Mariner sent out to search for them were ever to return.

Flight of 5 US Navy TBM Grumman Avengers (Not Flight 19)

The disappearance of the five Avengers and the PBM sparked one of the largest air and seas searches in history as hundreds of ships and aircraft combed over 200,00 square miles of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico, while, on land, search parties scoured the interior of Florida on the outside chance that the aircraft might have gone down there undetected.

But nothing was ever found. No wreckage, no bodies, nothing. All that remained were the elements of mystery and a mystery it quickly and easily became. Flight 19 "The Lost Patrol" is now the central element of the legend of the infamous "Bermuda Triangle." Much has been written and speculated about the Triangle, a stretch of ocean credited by some as being "the graveyard of the Atlantic," home of the forbidding Sargasso Sea. In actuality, the Triangle is no such geometric entity; it is an area whose northern boundaries stretch roughly from the southern Virginia coast to the Bermuda Islands, southward to the Bahamas and west to the Florida Keys. And within this area, it has been reported since 1840 that men, ships and even aircraft have disappeared with frequent regularity. Why? It depends on whom you talk to. Some claim that this Hoodoo Sea is a maritime Molech, that supernatural forces are at work there. Others assert that strange magnetic and natural forces unique to the area and unknown to modern science are responsible for the disappearances. Still more believe that with the heavy sea and air traffic moving through the area it is inevitable that some unexplained "incidents" are bound to happen. But no matter what the argument or rationale, there is something oddly provoking about these occurrences, particularly the "normal" circumstances which existed prior to each disaster. It is this writer's view that many a good tale would lie a-dying if all the facts were included.

Take the Lost Patrol, for example. The popular version inevitably goes something like this:

Five Avengers are airborne at 1400 on a bright sunny day. The mission is a routine two-hour patrol from Fort Lauderdale, Fla. due east for 150 miles, north for 40 miles and then return to base. All five pilots are highly experienced aviators and all of the aircraft have been carefully checked prior to takeoff. The weather over the route is reported to be excellent, a typical sunny Florida day. The flight proceeds. At 1545 Fort Lauderdale tower receives a call from the flight but, instead of requesting landing instructions, the flight leader sounds confused and worried. "Cannot see land," he blurts. "We seem to be off course."

"What is your position?" the tower asks.

There are a few moments of silence. The tower personnel squint into the sunlight of the clear Florida afternoon. No sign of the flight.

"We cannot be sure where we are," the flight leader announces. "Repeat: Cannot see land."

Contact is lost with the flight for about 10 minutes and then it is resumed. But it is not the voice of the flight leader. Instead, voices of the crews are heard, sounding confused and disoriented, "more like a bunch of boy scouts lost in the woods than experienced airmen flying in clear weather." "We can't find west. Everything is wrong. We can't be sure of any direction. Everything looks strange, even the ocean." Another delay and then the tower operator learns to his surprise that the leader has handed over his command to another pilot for no apparent reason.

Twenty minutes later, the new leader calls the tower, his voice trembling and bordering on hysteria. "We can't tell where we are . . .everything is . . .can't make out anything. We think we may be about 225 miles northeast of base . . ." For a few moments the pilot rambles incoherently before uttering the last words ever heard from Flight 19: "It looks like we are entering white water . . .We're completely lost."

Within minutes a Mariner flying boat, carrying rescue equipment, is on its way to Flight 19's last estimated position. Ten minutes after takeoff, the PBM checks in with the tower . . .and is never heard from again. Coast Guard and Navy ships and aircraft comb the area for the six aircraft. They find a calm sea, clear skies, middling winds of up to 40 miles per hour and nothing else. For five days almost 250,000 square miles of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf are searched. Yet, not a flare is seen, not an oil slick, life raft or telltale piece of wreckage is ever found.

Finally, after an extensive Navy Board of Inquiry investigation is completed, the riddle remains intact. The Board's report is summed up in one terse statement: "We are not able to even make a good guess as to what happened."

Maybe not, but let's try. Popular versions of the story of the Lost Patrol such as the preceding tale bear striking resemblances to one another, so much so that, because of re-occurring passages in all of them, one is led to believe that a certain amount of borrowing and embellishing from a single source has been performed over the 28 years since the incident occurred. And let us say now that this article is not a debunking piece, but simply a perusal of an incident that has grown to the stature of a myth a legend that begs to be more expertly examined.

The following account is based on the official Board of Inquiry report concerning the disappearance of Flight 19 and PBM-5, Buno 59225. The record consists of testimony of individuals, expert opinions and logs of the numerous radio transmissions.

To begin with, the Lost Patrol was not a patrol at all. It was an over water navigation training hop composed of an instructor, four Naval Aviators undergoing VTB-type advanced training and nine enlisted aircrewmen who, with the exception of one, were all undergoing advanced combat aircrew training in VTB-type aircraft. The instructor was a combat veteran with 2509.3 hours of flying time, most of it in type, while his students had approximately 300 hours each, about 60 in the TBM/TBF. With the exception of the instructor, hardly a "highly experienced" lot.

The flight was entitled Navigation Problem No. 1 which ran as follows: (1) depart NAS Fort Lauderdale 26 degrees 03 minutes north and 80 degrees 07 minutes west and fly 091 degrees distance 56 miles to Hens and Chickens Shoals to conduct low level bombing and, after bombing, continue on course 091 for 67 miles, (2) fly course 346 degrees for 73 miles and (3) fly course 241 degrees for a distance of 120 miles, returning to NAS Fort Lauderdale. In short, a triangular route with a brief stop for some glide bombing practice on the first leg out.

Prior to the hop, the five Avengers were thoroughly preflighted. All survival gear was intact, fuel tanks were full, instruments were checked -but one mechanic commented that none of the aircraft had a clock. Of the 24-hour variety, clocks normally installed aboard aircraft were highly prized by souvenir hunters. Besides, everyone had his own personal wristwatch - or did he? Inside the training office, the students of Flight 19 waited for their briefing; they were going to be late- takeoff time was set for 1345 and the instructor hadn't shown up. At 1315 he arrived and asked the aviation training duty officer to find another instructor to take his place. Giving no reason, he stated simply that he did not want to take this one out. His request was denied; he was told that no relief was available.

It was the instructor's first time on this particular syllabus hop. He had only recently arrived from NAS Miami (where he had also been a VTB-type instructor). But to the anxiously waiting students, it was the third and final navigational problem. The previous two had been in the same general area and now they were anxious to complete the phase.

At last the briefing began. The weather for the area of the problem was described as "favorable." In the words of the training duty officer who attended the briefing, "The aerologist sends us a report in the morning. If weather conditions are unfavorable, he will inform us . . . and tell us about the condition. In the absence of any further information I considered the weather favorable." This estimate was later confirmed hy another TBM training flight performing the same problem an hour earlier than Flight 19: weather favorable, sea state moderate to rough.

At 1410 the flight was in the air, led by one of the students. The instructor, whose call sign was Fox Tare Two Eight (FT-28), flew the rear, in a tracking position. ETA was 1723 and the TBMs had enough fuel to remain aloft for five to five-and-a-half hours. Hens and Chickens Shoals, commonly called Chicken Rocks, the point at which they would conduct low level bombing, was only 56 miles away. If they cruised at 150 mph, they would arrive at the Rocks in about 20 minutes or so. Thirty minutes for bombing and then continue on the final 67 miles of the first leg. At Fort Lauderdale, the tower picked up conversation from Flight 19: "I've got one more bomb." "Go ahead and drop it" was the response. A fishing boat captain working near the target area remembers seeing three or four airplanes flying east at approximately 1500.

Assuming that the flight flew the rest of the first leg and then changed to course 346, they would have been near Great Sale Cay by 1540. But at about that time, FT-74, the senior flight instructor at Fort Lauderdale. was joining up his squadron around the field when he heard what he assumed were either some boats or aircraft in distress. "One man was transmitting on 4805 to 'Powers' [the name of one of the students]." The voice asked Powers what his compass read a number of times and finally Powers said, "I don't know where we are. We must have got lost after that last turn."

Upon hearing this, the senior flight instructor informed Fort Lauderdale that either a boat or some planes were lost. He then called, "This is FT-74, plane or boat calling 'Powers' please identify yourself so someone can help you." No response but, a few moments later, the voice came on again asking the others if there were any "suggestions." FT-74 tried again and the voice was identified as FT-28. "FT-28, this is FT-74, what is your trouble?" "Both my compasses are out and I am trying to find Fort Lauderdale, Fla. I am over land but it's broken. I am sure I'm in the Keys but I don't know how far down and I don't know how to get to Fort Lauderdale."

The Keys? Both compasses out? FT-74 paused and then told FT-28 to ". . . put the sun on your port wing if you are in the Keys and fly up the coast until you get to Miami. Fort Lauderdale is 20 miles further, your first port after Miami. The air station is directly on your left from the port." But FT-28 should have known if he was actually over the Keys; he had flown in that area for six months while stationed at Miami. He sounded rattled, confused.

"What is your present altitude? I will fly south and meet you." FT-28 replied, "I know where I am now. I'm at 2300 feet. Don't come after me." But FT-74 was not convinced. "Roger, you're at 2300. I'm coming to meet you anyhow." Minutes later, FT-28 called again: "We have just passed over a small island. We have no other land in sight." How could he have run out of islands? How could he have missed the Florida peninsula if he was in the Keys? FT-74 was beginning to have serious doubts.

FT-28 came back on the air. "Can you have Miami or someone turn on their radar gear and pick us up? We don't seem to be getting far. We were out on a navigation hop and on the second leg I thought they were going wrong, so I took over and was flying them back to the right position. But I'm sure, now, that neither one of my compasses is working." FT-74 replied: "You can't expect to get here in ten minutes. You have a 30- to 35-knot head or crosswind. Turn on your emergency IFF gear, or do you have it on?" FT-28 replied that he did not.

At 1626 Air-Sea Rescue Task Unit Four at Fort Everglades heard FT-28: "I am at angels 3.5. Have on emergency IFF. Does anyone in the area have a radar screen that could pick us up?" ASRTU-4 Rogered and, not having direction-finding gear, contacted Fort Lauderdale, who replied that they would notify NAS Miami and ask the other stations to attempt to pick up the lost flight on radar or with direction finders. In all, more than 20 land facilities were contacted to assist in the location of Flight 19. Merchant ships in the area were asked to be on the alert and several Coast Guard vessels were told to prepare to put to sea. But there were delays. Teletype communication with several locations was out and radio fixes were hampered by static and interference from Cuban broadcast stations.

At 1628, ASRTU-4 called FT-28 and suggested that another plane in the flight with a good compass take over the lead. FT-28 Rogered but, from fragmentary messages between the flight leader and the students concerning their estimated position and headings, it appears that no other plane took the lead at this time.

Meanwhile, FT-74 was having his own problems maintaining contact with the lost flight. "Your transmissions are fading. Something is wrong. What is your altitude?" From far away, FT-28 called, "I'm at 4500 feet." At this point FT-74's transmitter went out and he had no power to continue on the common frequency with the lost Avengers.

According to the senior instructor's later testimony, ". . . as his transmissions were fading, he must have been going away north as I headed south. I believe at the time of his first transmission, he was either over the Biminis or Bahamas. I was about 40 miles south of Fort Lauderdale and couldn't hear him any longer."

Did he remember any more? Yes, he recalled that at 1600, FT-28 had reported that he had a visibility of 10 to 12 miles. FT-74 further stated that while flying offshore at the time, he had observed a very rough sea covered with white caps and streamers. (The surface winds were westerly, about 22 knots, and visibility was very good in all directions except directly west.)

Upon returning to Fort Lauderdale, FT-74 went to operations and related as much as he could remember of the conversations with FT-28 to the duty officer and requested permission to take the duty aircraft out to search for the flight. Receiving no answer, the pilot then made the same request to the flight officer who replied, "Very definitely, no."

The flight officer had been notified of Flight 19's difficulty at 1630 by the duty officer. "I immediately went into operations and learned that the flight leader thought he was along the Florida Keys. I then learned that his first transmission revealing that he was lost had occurred around 1600. I knew by this that the leader could not possibly have gone on more than one leg of his navigation problem and still gotten back to the Keys by 1600. . . . I notified ASRTU-4 to instruct FT-28 to fly 270 degrees and also to fly towards the sun." (This was standard procedure for lost planes in the area and was drummed into all students.)

At 1631, ASRTU-4 picked up FT-28. "One of the planes in the flight thinks if we went 270 degrees we could hit land."

At 1639, the Fort Lauderdale operations officer contacted ASRTU-4 by telephone. He concurred with FT-74 and felt that the flight must be lost over the Bahama Bank. His plan was to dispatch the Lauderdale ready plane, guarding 4805 kc, on a course 075 degrees to try to contact FT-28. If communications improved during the flight, the theory would be proved and relay could be established.

Operations requested that ASRTU-4 ask FT-28 if he had a standard YG (homing transmitter card) to home in on the tower's direction finder. The message was sent but was not Rogered by FT-28. Instead, at 1645, FT-28 announced: "We are heading 030 degrees for 45 minutes, then we will fly north to make sure we are not over the Gulf of Mexico."

Meanwhile no bearings had been made on the flight. IFF could not be picked up. The lost flight was asked to broadcast continuously on 4805 kc. The message was not Rogered. Later, when asked to switch to 3000 kc, the search and rescue frequency, FT-28 called: "I cannot switch frequencies. I must keep my planes intact."

At 1656, FT-28 did not acknowledge a request to turn on his ZBX (the receiver for the YG) but, seven minutes later, he called to his flight, "Change course to 090 degrees for 10 minutes." At approximately the same time, two different students were heard; "Dammit, if we could just fly west we would get home; head west, dammit."

By 1700, the operations officer was about to send the duty plane out to the east when he was informed that a radio fix was forthcoming the aircraft was held on the ground pending the fix. At 1716, FT-28 called out that they would fly 270 degrees "until we hit the beach or run out of gas."

In the meantime, Palm Beach was reporting foul weather and, at Fort Lauderdale, they waited for it to move in. At 1724, FT-28 called for the weather at Fort Lauderdale: clear at Lauderdale; over the Bahamas cloudy, rather low ceiling and poor visibility.

By 1736, it was decided that the ready plane at Fort Lauderdale would not go out. According to the operations officer, the prospect of bad weather and the encouraging information that FT-28 was going to "fly west until they hit the beach" prompted his decision. It was for this reason that the senior instructor's request was turned down.

The decision was logically correct; but with hindsight, it was ironic and lamentable. To this day, FT-74 is convinced he knew where the lost flight had to be. He was denied the opportunity to prove his point. For reasons of safety and, perhaps, hopeful confidence, it was determined that the single-engine, single-piloted ready plane would not be risked on an arbitrary flight into the gathering darkness over winter seas.

At 1804, FT-28 called to his flight, "Holding course 270 degrees we didn't go far enough east . . .we may as well just turn around and go east again." The flight leader was apparently still vacillating between his idea that they were over the Gulf and his students' belief that they were over the Atlantic.

The Gulf and Eastern Sea Frontier HF/DF nets had now completed triangulation of bearings on FT-28 from six different radio stations, which produced a reliable fix: he was within an electronic 100-mile radius of 29 degrees north, 79 degrees west; Flight 19 was north of the Bahamas and east of the Florida coast. All stations were alerted and instructed to turn on field lights, beacons and searchlights. Unfortunately, no one. thought to advise the activities assisting in the attempted recovery of Flight 19 to make open, or "blind" transmissions of the 1750 evaluated fix to any aircraft of the distressed flight!

At 1820 a PBY was airborne out of CGAS Dinner Key to try to contact the flight. No luck. Transmitter antenna trouble. But garbled messages were still coming in from FT-28. "All planes close up tight . . .we'll have to ditch unless landfall . . .when the first plane drops below 10 gallons, we all go down together."

At about the same time, the master of the British tanker Viscount Empire, passing through the area northeast of the Bahamas en route to Fort Lauderdale, reported to ASRTU-4 that she encountered tremendous seas and winds of high velocity in that area.

More multi-engine search aircraft were dispatched by air stations up and down the Florida coast.

At NAS Banana River, two PBM-5s were being prepared to join the search, after being diverted from a regularly scheduled night navigation training flight. A flight mech checked out one of the planes, PBM-5 BuNo 59225, filled it with enough fuel for a 12-hour flight and, as he later testified before the Board, "I found it to be A-1. I spent about an hour in the aircraft . . .and there was no indication of any gas fumes. There was no discrepancy in any of the equipment and, when we started up the engines, they operated normally."

According to the pilot of the other PBM, "About 1830, operations called and the operations duty officer in regard to the five TBMs whose last position was reported as approximately 130 miles east of New Smyrna with about 20 minutes of fuel remaining. We received this position and were told to conduct a square search. We were instructed to conduct radar and visual search and to stand by on 4805 kc, the reported frequency on which the TBMs were operating. At the time we were briefed, Ltjg Jeffrey, in Training 49, was to make the second plane in the search. No other planes were included."

Were any plans made for a joint conduct of the search mission? "Yes, I was to proceed to the last reported position of the TBMs and conduct a square search. Lt. Jeffrey was to proceed to New Smyrna and track eastward to intercept the presumed track of the TBMs and then was to conduct an expanding square search at the last reported position of the TBMs."

What were the weather and sea conditions when you arrived in the vicinity of 29 degrees north, 79 degrees west? ". . .the ceiling was approximately 800 to 1200 feet overcast, occasional showers, estimated wind, west southwest about 25 30 knots. The air was very turbulent. The sea was very rough."

At 1927, PBM-5, Buno 59225, was airborne from Banana River with 3 aviators aboard and a crew of 10. At 1930, the aircraft radioed an "out" report to its home base and was not heard from again.

Cruising off the coast of Florida, the Type T2 tanker S.S. Gaines Mills was sailing through the dark night when it sent the following message, "At 1950, observed a burst of flames, apparently an explosion, leaping flames 100 feet high and burning for ten minutes. Position 28 degrees 59 minutes north, 80 degrees 25 minutes west. At present, passing through a big pool of oil. Stopped, circled area using searchlights, looking for survivors. None found." Her captain later confirmed that he saw a plane catch fire and immediately crash, exploding upon the sea.

A message from USS Solomons (CVE 67), which was participating in the search, later confirmed both the merchantman's report and the fears of many at Banana River. "Our air search radar showed a plane after takeoff from Banana River last night joining with another plane, (the second PBM) then separating and proceeding on course 045 degrees at exact time S.S. Gaines Mills sighted flames and in exact spot the above plane disappeared from the radar screen and never reappeared." No wreckage was sighted and according to witnesses there was little likelihood that any could have been recovered due to a very rough sea. The next day, water samples, taken in the area, developed an oily film. The area was not buoyed due to the heavy seas nor were diving or salvage operations ever conducted. The depth of the water was 78 feet and the site was close to the Gulf Stream.

During the Board's examination of the disappearance of the PBM, several witnesses were questioned concerning gas fumes and smoking regulations, which were reportedly well posted and rigidly enforced aboard all PBMs. Although the Board's report is not a verbatim record and no accusations were made, there seems to be enough inference present to cause one to suspect that the Board was aware of the PBM's nickname, "the flying gas tank."

What followed is essentially what has been reported by so many others: five days of fruitless searching which revealed numerous older wrecks but not so much as a scrap of wreckage from either the TBMs or the PBM. The fate of the latter seems confirmed an in-flight fire of unknown origin and subsequent crash/explosion. The former's disappearance still has the aura of mystery, however.

Why did FT-28 not want to go on the flight; what was his state of mind? How could both his compasses have gone out? Did he have a watch? One suspects he did not, as he repeatedly asked the other flight members how long certain headings had been flown. These are only some of the questions which can never be fully answered.

But some have been.

We now know that FT-28 took the lead sometime after the turn north on the second leg, thinking that his students were on a wrong heading. We know that FT-28 would not switch to the emergency radio frequency for fear of losing contact with his flight. We also know that there were strong differences of opinion between the instructor and the students about where they were. The instructor, familiar with the Florida Keys, with both compasses out and with evidently no concept of time, could very well have mistaken the cays of the northern Bahamas for the Keys and the water beyond for the Gulf of Mexico.

But the students, having flown the area before, appeared to know exactly where they were and it was not the Keys or the Gulf. The lead passed back and forth between FT-28 and a student, and land was never reached as the flight zigzagged through the area north of the Bahamas.

Toward the end, the low ceiling and daytime ten-mile visibility were replaced by rain squalls, turbulence and the darkness of winter night. Terrific winds were encountered and the once tranquil sea ran rough. They would "fly towards shore," the better to be rescued.

Valiantly trying to keep his flight together in the face of most difficult flying conditions, the leader made his plan: When any aircraft got down to ten gallons of fuel, they would all ditch together. When that fateful point was reached, we can only imagine the feelings of the 14 men of Flight 19 as they descended through the dark toward a foaming, raging sea and oblivion.

Former TBM pilots that we questioned express the opinion that an Avenger attempting to ditch at night in a heavy sea would almost certainly not survive the crash. And this, we feel, was the case with Flight 19, the Lost Patrol. The aircraft most probably broke up on impact and those crewmen who might have survived the crash would not have lasted long in cool water where the comfort index was lowered by the strong winds. This last element, while only an educated guess, seems to satisfy this strange and famous "disappearance."

-------

Recent posts include:

"The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 1)"

"The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 3)"

"Neolithic Settlement of Stonehenge Builders Found (+Video)"

"Antikythera: Enigma of Ancient Computer Resolved At Last"

Technorati: bermuda triangle, bbc, video, uss, cyclops, flight 19, loss, lost, devil, triangle, bermuda, nasa, miami, florida, puerto rico, avenger, weather, sea, aircraft, radio, martin, mariner, nas

Add to: CiteUlike | Connotea | Del.icio.us | Digg | Furl | Newsvine | Reddit | Yahoo

Tuesday, February 20, 2007

The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 1)

'The Bermuda Triangle: Beneath the Waves' - An online BBC* Television Documentary which includes a dramatic re-enactment of the disappearance of 'Flight 19' (see the background info below) and appearances by Richard Winer and Phil Beck.

"..Over the last century a thousand ships have been reported lost without a trace in the Bermuda Triangle. Using state-of-the-art technology, we're going to unlock one of the Ocean's deepest secrets. Can science prove if a recently discovered natural phenomenon could be dragging ships down to a watery grave?

..and we'll reveal a new mystery that until now was unexplained. Here, the truth can be far stranger than fiction. There are powerful, some would say evil, forces at work out here. Since 1492 when Christopher Columbus first sailed into the area and saw strange lights in the sky, the list of bizarre disappearences in the Bermuda Triangle has grown. Thousands of ships and planes have simply vanished without a trace.."

Watch the video here:

*Listen here to Quentin Cooper's Material World from The Edinburgh Science Festival (first broadcast Thursday 13 April 2006):

"Gas hydrates are a potentially huge and largely untapped source of energy, but they could also be a huge environmental threat as a source of greenhouse gases, a cause of tsunamis and possibly the cause of the strange disappearances in the Bermuda Triangle." (Relevant section begins 16 minutes into the program). [Methane]

-------

The following information is courtesy of the US Naval Historical Center:

1) Bermuda Triangle Fact Sheet (This post)

2) History of USS Cyclops + Images (This post)

"The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 2)" contains:

3) The Loss Of Flight 19

4) "Lost Patrol"

"The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 3)" contains:

5) In Search of.. The Bermuda Triangle (Video - Leonard Nimoy)

6) "Exorcizing the Devil's Triangle"

-------

1) Bermuda Triangle Fact Sheet

Prepared by the U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters and the Naval Historical Center

The U. S. Board of Geographic Names does not recognize the Bermuda Triangle as an official name and does not maintain an official file on the area.

The "Bermuda or Devil's Triangle" is an imaginary area located off the southeastern Atlantic coast of the United States, which is noted for a high incidence of unexplained losses of ships, small boats, and aircraft. The apexes of the triangle are generally accepted to be Bermuda, Miami, Florida, and San Juan, Puerto Rico.

In the past, extensive, but futile Coast Guard searches prompted by search and rescue cases such as the disappearance of a flight of five TBM Avengers shortly after take off from Fort Lauderdale, Florida ('Flight 19' - see Part 2), or the traceless sinking of USS Cyclops* and Marine Sulphur Queen (2001 Dive Report) have lent credence to the popular belief in the mystery and the supernatural qualities of the "Bermuda Triangle."

Countless theories attempting to explain the many disappearances have been offered throughout the history of the area. The most practical seem to be environmental and those citing human error. The majority of disappearances can be attributed to the area's unique environmental features. First, the "Devil's Triangle" is one of the two places on earth that a magnetic compass does point towards true north. Normally it points toward magnetic north. The difference between the two is known as compass variation. The amount of variation changes by as much as 20 degrees as one circumnavigates the earth. If this compass variation or error is not compensated for, a navigator could find himself far off course and in deep trouble.

An area called the "Devil's Sea" by Japanese and Filipino seamen, located off the east coast of Japan, also exhibits the same magnetic characteristics. It is also known for its mysterious disappearances.

Another environmental factor is the character of the Gulf Stream. It is extremely swift and turbulent and can quickly erase any evidence of a disaster. The unpredictable Caribbean-Atlantic weather pattern also plays its role. Sudden local thunder storms and water spouts often spell disaster for pilots and mariners. Finally, the topography of the ocean/sea- floor varies from extensive shoals around the islands to some of the deepest marine trenches in the world. With the interaction of the strong currents over the many reefs the topography is in a state of constant flux and development of new navigational hazards is swift.

Not to be under estimated is the human error factor. A large number of pleasure boats travel the waters between Florida's Gold Coast and the Bahamas. All too often, crossings are attempted with too small a boat, insufficient knowledge of the area's hazards, and a lack of good seamanship.

The Coast Guard is not impressed with supernatural explanations of disasters at sea. It has been their experience that the combined forces of nature and unpredictability of mankind outdo even the most far fetched science fiction many times each year.

We know of no maps that delineate the boundaries of the Bermuda Triangle. However, there are general area maps available through the Distribution Control Department, U.S. Naval Oceanographic Office, Washington, D.C. 20390. Of particular interest to students if mysterious happenings may be the "Aeromagnetic Charts of the U.S. Coastal Region," H.O. Series 17507, 15 sheets. Numbers 9 through 15 cover the "Bermuda Triangle."

Interest in the "Bermuda Triangle" can be traced to

(A) the cover article in the August 1968 Argosy, "The Spreading Mystery of the Bermuda Triangle",

(B) the answer to a letter to the editor of the January 1969 Playboy, and

(C) an article in August 4, 1968 I, "Limbo of Lost Ships", by Leslie Lieber.

Also, many newspapers carried a December 22, 1967 National Geographic Society news release which was derived largely from Vincent Gaddis' Invisible Horizons: True Mysteries of the Sea (Chilton Books, Philadelphia, 1965. OCLC# 681276)

Chapter 13, "The Triangle of Death", in Mr. Gaddis' book, presents the most comprehensive account of the mysteries of the Bermuda Triangle. Gaddis describes nine of the more intriguing mysteries and provides copious notes and references. Much of the chapter is reprinted from an article by Mr. Gaddis, "The Deadly Bermuda Triangle", in the February 1964 Argosy.

The article elicited a large and enthusiastic response from the magazine's readers. Perhaps the most interesting letter, which appeared in the May 1964 Argosy's "Back Talk" section, recounts a mysterious and frightening incident in an aircraft flying over the area in 1944.

-------

2) History of USS Cyclops + Images

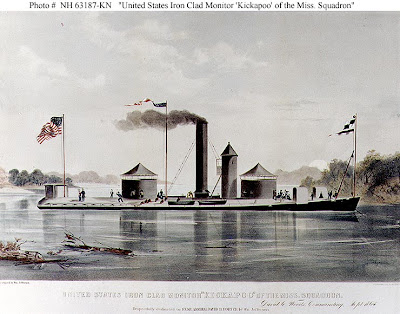

The ironclad steamer Kickapoo** carried the name Cyclops from 15 June to 10 August 1869, then was renamed Kewaydin.

The second Cyclops, a collier*, was launched 7 May 1910 by William Cramp and Sons, Philadelphia, Pa., and placed in service 7 November 1910, G. W. Worley, Master, Navy Auxiliary Service, in charge. Operating with the Naval Auxiliary Service, Atlantic Fleet, the collier voyaged in the Baltic during May to July 1911 to supply 2d Division ships. Returning to Norfolk, she operated on the east coast from Newport to the Caribbean servicing the fleet. During the troubled conditions in Mexico in 1914 and 1915, she coaled ships on patrol there and received the thanks of the State Department for cooperation in bringing refugees from Tampico to New Orleans.

With American entry into World War I, Cyclops was commissioned 1 May l917, Lieutenant Commander G. W. Worley in command. She joined a convoy for St. Nazaire, France, in June 1917, returning to the east coast in July. Except for a voyage to Halifax, Nova Scotia, she served along the east coast until 9 January 1918 when she was assigned to Naval Overseas Transportation Service. She then sailed to Brazilian waters to fuel British ships in the south Atlantic, receiving the thanks of the State Department and Commander-in-Chief, Pacific. She put to sea from Rio de Janiero 16 February 1918 and after touching at Barbados on 3 and 4 March, was never heard from again. Her loss with all 306 crew and passengers, without a trace, is one of the sea's unsolved mysteries.

*Collier: full load displacement 19,360; length 542'; beam 65'; draft 27'8"; speed 15 knots.; complement 236

USS Cyclops (1910-1918)

Photographed by the New York Navy Yard, probably while anchored in the Hudson River, NY, on 3 October 1911.

Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives.

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

USS South Carolina (BB-26) and USS Cyclops (1910-1918)

Engaged in an experimental coaling while under way at sea in 1914. Rigging between the two ships was used to transfer two 800-pound bags of coal at a time. The bags were landed on a platform in front of the battleship's forward 12-inch gun turret, and then carried to the bunkers.

The donor, who served as a seaman in South Carolina at the time, comments: "it showed that this was possible but a very slow method of refueling. Nothing was heard of the test afterwards."

Donation of Earle F. Brookins, Jamestown, NY, 1972.

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

Roy Stuart Merriam,

Coxwain, U.S. Navy

Who was lost with USS Cyclops in March 1918.

His cap band is from USS San Diego (ACR-6).

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

Earnest Randolph Crammer,

Seaman, U.S. Navy

Who was lost with USS Cyclops in March 1918.

His cap band is from that ship.

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

-------

**USS Kickapoo, a 1300-ton Milwaukee class double-turret ironclad river monitor, was built at Carondelet, Missouri, and commissioned in July 1864. She served off the mouth of the Red River, Louisiana, until October, when she was assigned to the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. Kickapoo was then sent to Mobile Bay, Alabama, to support the campaign against the city of Mobile. She took part in mine clearance and bombardment operations in the spring of 1865, helping to rescue crewmen from the monitors Milwaukee and Osage when they were sunk by Confederate mines. In June 1865, Kickapoo went to New Orleans, where she was decommissioned in July. She was twice renamed in 1869, becoming Cyclops in June and Kewaydin in August. The ship was sold in September 1874.

USS Kickapoo (1864-1874)

Color lithograph by J.H. Bufford after an original drawing by William Jefferson, circa 1864. It is entitled "The United Stated Iron Clad Monitor 'Kickapoo' of the Miss. Squadron. David G. Woods, Commanding, Sept. 1864" and is dedicated to Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter by William Jefferson.

Courtesy of the U.S. Navy Art Collection, Washington, D.C.

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

-------

Recent posts include:

"The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 2)"

"The Bermuda Triangle - BBC Video + Info (Part 3)"

"Ancient coin challenges myth of Cleopatra's beauty (+ related video)"

"Neolithic Settlement of Stonehenge Builders Found (+Video)"

"Antikythera: Enigma of Ancient Computer Resolved At Last"

Technorati: bermuda, triangle, bbc, television, documentary, disappearance, flight 19, ships, lost, technology, ocean, secrets, science, natural, phenomenon, mystery, columbus, video, gas, hydrates, greenhouse, gases, tsunamis, methane, uss, cyclops, devil, us, coast guard, miami, puerto rico, navigation hazards, sea, floor, topography, thunder storms, water spouts, mysteries

Add to: CiteUlike | Connotea | Del.icio.us | Digg | Furl | Newsvine | Reddit | Yahoo